CAR-T reshaped cancer treatment. Can it change autoimmune disease, too?

More than 15 years ago, Aimee Payne was searching for a way to hunt down — and target — the cells behind a potentially life-threatening condition that initially triggers painful blisters on the skin.

The University of Pennsylvania dermatologist found an answer in another corner of the university that housed cancer experts looking to solve a different problem.

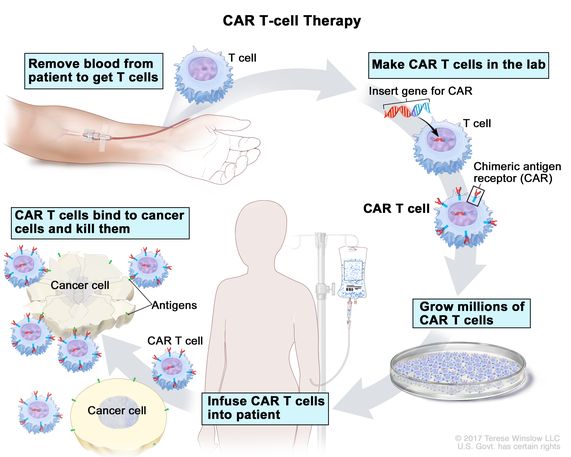

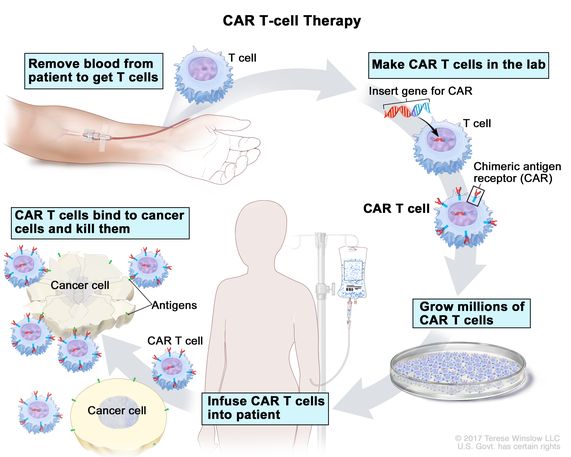

A team of researchers, led by immunologist Carl June, genetically altered the T cells of three leukemia patients who had failed to respond to standard cancer therapies. Reinfusing the engineered cells back into the patients appeared to cure two of them and the other patient improved. The seminal results, published in 2011, opened up a new field, dubbed chimeric antigen receptor T cells, or CAR-T, that has produced six approved cancer therapies.

The University of Pennsylvania dermatologist found an answer in another corner of the university that housed cancer experts looking to solve a different problem.

A team of researchers, led by immunologist Carl June, genetically altered the T cells of three leukemia patients who had failed to respond to standard cancer therapies. Reinfusing the engineered cells back into the patients appeared to cure two of them and the other patient improved. The seminal results, published in 2011, opened up a new field, dubbed chimeric antigen receptor T cells, or CAR-T, that has produced six approved cancer therapies.

While CAR-T continues to reshape cancer care, enthusiasm is growing for its move into a less-obvious area: autoimmune disease. Working with one of the CAR-T inventors in 2016, Payne’s lab created an alternative form of engineered T cells that, when given to mice, killed only the B cells that were to blame for the skin disease, called pemphigus vulgaris.

After CAR-T developers, solely focused on cancer at the time, turned her down, Payne co-founded a company, Cabaletta Bio, that started a Phase I clinical trial for patients with the skin disorder.

The company now finds itself in a very different place. The push for CAR-T into autoimmune diseases is gaining steam thanks to scientific advances, clinical trial partnerships, and more recently, promising, if early, clinical data.

“It’s really one of the hottest areas for clinical research right now,” Payne said.

More biotechs — and the pharmaceutical giant Novartis — are bringing their CAR-T therapies to the clinic over the next year to see if the promising results hold up in a broader array of autoimmune disorders.

The move comes as scientists and drugmakers, inspired by the dramatic successes of immuno-oncology, take the lessons they have learned about co-opting the immune system to attack cancer and redirect them to diseases of the immune system itself. Vast potential exists to tackle more than 80 autoimmune conditions that collectively affect tens of millions of people. And researchers say the use of CAR-T in autoimmune diseases could lead to much fewer side effects than what’s been observed in cancer.

But a one-time infusion of CAR-T cells still costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, and even then, companies don’t always make enough of the cells in time to reach patients. These manufacturing and price issues must be addressed before realizing lofty dreams of transforming the treatment paradigm.

From fringe to mainstream

When June and his collaborators at Penn published their landmark paper more than 10 years ago on the trio of chronic lymphoid leukemia patients, a new age of medicine had arrived in the mind of Marko Radic.

His amazement coincided with a personal reckoning. Radic, an associate professor at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, realized his research on autoimmune disease mechanisms was not translating directly into new medicines for these conditions.

The desire to do more was especially acute when speaking with lupus patients who had limited options to deal with pain, fever, rashes and all sorts of symptoms as their immune systems attack their own tissues and organs — and who had been repeatedly disappointed by negative clinical results around new drugs.

He speculated that engineered T cells, such as what June used, can kill the B cells that were believed to trigger autoimmune attacks in lupus patients. Doing so, the thinking went, would reset the immune system. Antibodies couldn’t do the job thoroughly enough, he had found.

Radic said he ran into “quite a bit of skepticism” at the NIH, which declined his grant proposals. But thanks to a $300,000 grant from the Lupus Research Alliance in 2015, he began testing a CAR-T construct in mice with lupus. Just like the CAR-T candidates being tested for cancer at the time, this one was also designed to target CD19, a marker found not only on cancerous B cells but all B cells.

“I was really just pushing almost blindly forward,” he said. But it worked: The CAR-T cells cleared all B cells from mice and kept the disease under control.

His research, published in 2019, paved the way for a German team, led by Georg Schett, to open a clinical study at the University Hospital Erlangen to try the same idea in patients. Five patients with refractory systemic lupus erythematosus — for whom the previous immunosuppressive treatments didn’t work — were given a CD19-targeting CAR-T. All five went into remission.

“There are times within a community, within a therapeutic area, where there are pivot points or there are things that we can look back on and say, ‘Yes, this made a difference,’” said Stacie Bell, who leads the Lupus Research Alliance’s clinical research affiliate. “By all means, Dr. Schett’s publication is going to be one of those.”

Kyverna Therapeutics, which raised $110 million to develop CAR-T for autoimmune conditions, is sponsoring an expansion of Schett’s study to include 20 patients with different autoimmune diseases, including myositis and scleroderma. It’s part of a larger plan to move into many autoimmune diseases.

The company’s own CD19 CAR-T therapy has been cleared to start a clinical trial this year.

“What has been missing in cell therapy is the large indication,” said CEO Peter Maag. “We’re the large indication.”

Novartis, which had steered June’s original CAR-T therapy toward a historic blood cancer approval in 2017, has also aimed its new drug candidate at lupus patients. It has begun enrollment in a Phase I/II clinical trial, marking the pharmaceutical giant’s first foray deploying CAR-T in autoimmune disease. In a recent analyst call, CEO Vas Narasimhan called the move “our top priority for CAR-T.”

“It makes good scientific sense if you think about a product with a demonstrated mechanism of action, in this case B cell depletion, and how you build on that and leverage your manufacturing capabilities to reach more patients where the science continues to make sense,” said Jen Brogdon, head of cell and gene therapies at the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, in an interview.

She cautioned that more testing is needed to rule out unexpected long-term results. In a previous trial testing a drug for lupus, patients went into remission but later relapsed — and their flares became even worse.

The company is also exploring CAR-T possibilities in solid tumors, which for many initially seemed like the obvious choice for where the technology should focus next. But these trials have been beset by serious side effects or disappointing results, and Brogdon said her team needs to be “realistic and pragmatic” about where to invest.

Some believe autoimmune diseases now appear to be the better place for CAR-T to showcase its potential, with opportunities not just to repurpose the original CD19 CAR-T but also design bespoke ones.

“Rather than asking the T cell to now kill a totally different type of cell, like a colon cancer cell or a breast cancer cell or something like that, maybe the best other question is: What other type of B cells can we tell the CAR-T cells to kill?” said Payne, the University of Pennsylvania researcher.

Payne’s startup, Cabaletta, has recently begun developing a CD19 CAR-T in collaboration with Schett. But the company uses a slightly different acronym: CAAR-T, or chimeric autoantibody receptor T cells, to describe its other therapy candidates. By selectively targeting only subsets of B cells, the company’s technology aims to clear out problematic B cells while keeping healthy B cells — what Payne called a “laser surgical approach” compared to the one-time systemic reset triggered by CD19 CAR-Ts.

Others are leveraging a special subtype of T cells known as regulatory T cells, or Tregs, which Jason Fontenot, chief scientific officer at Sangamo Therapeutics, described as firefighters or peacekeepers of the immune system. In contrast, traditional CAR-T is based on effector T cells that would rather set off fires in order to kill foreign invaders, but also risk inflammation.

The biotech started a clinical trial in 2022 to see if its lead CAR-Treg candidate can prevent recipients of a kidney transplant from rejecting the donor organ while keeping the rest of their immune system intact. It would act as an alternative for conventional immunosuppressants, which can leave patients vulnerable to infections.

If CAR-Tregs prove successful, developers say they can broaden the impact of CAR-T to other big autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes.

Buddy system with oncologists

Cabaletta’s first-of-its-kind study hasn’t been without anxiety.

For all its promises, one of the greatest fears that autoimmune specialists have when it comes to deploying CAR-T is that they could run into the same aggressive immune responses that plagued the use of CAR-T in oncology and, at one point, threatened to halt its development.

Those severe, potentially fatal side effects — namely cytokine release syndrome, or CRS, and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome, or ICANS — happen when CAR-T’s killing of cancer cells sets off the alarm in other parts of the immune system, which then unleashes a cascade of inflammatory reactions.

Oncologists have come up with ways to mitigate these side effects, such as prescribing anti-inflammatory drugs. In theory, the risks of CRS and ICANS are also lower for autoimmune disease, as the CAR-T would be killing fewer cells than in cancer, which is defined by uncontrolled growth of malignant cells, said Peter Merkel, a rheumatologist at the University of Pennsylvania.

Still, “we didn’t know what to expect in the very first patient,” Payne said. As an extra safeguard, dermatologists at the University of Pennsylvania teamed up with oncologists at the institution who are versed in CAR-T. They pooled expertise to draft the clinical trial protocol in one of the first examples of a buddy system that investigators say is crucial for testing CAR-T in autoimmune disease.

Once the patients were referred to the cell therapy center, had their cells taken out, genetically modified and reinfused, the expertise of the oncologists came into play. They monitored the pemphigus vulgaris patients for any signs of the side effects that they have come to know well from treating cancer patients — and administered the necessary care to alleviate those symptoms.

The results, so far, show no dose-limiting toxicities, nor serious side effects. Out of 16 patients, there was one case of a patient with grade 1 cytokine release syndrome, meaning a fever and potentially vomiting and nausea.

Plans call for many more CAR-T trials in different autoimmune diseases, according to David Porter, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s cell therapy center, who had led the first CAR-T trial in oncology as well as Cabaletta’s trial.

“If this can work,” Porter said, “there really are limitless approaches, and the number of patients that potentially could benefit is enormous.”

Comments

Post a Comment